We tried three different accompaniment patterns for our tune, with an alternative set of chords from week one – each player picked a note from each chord, linking them together to create their own personalised part.

Looking at the PDF below, A is the short stabs, B has the overlapping patterns used earlier in the term and C is the feature rhythm for the A section only. All are illustrated with the A section and the notes used are also illustrative, please use your own chosen notes:

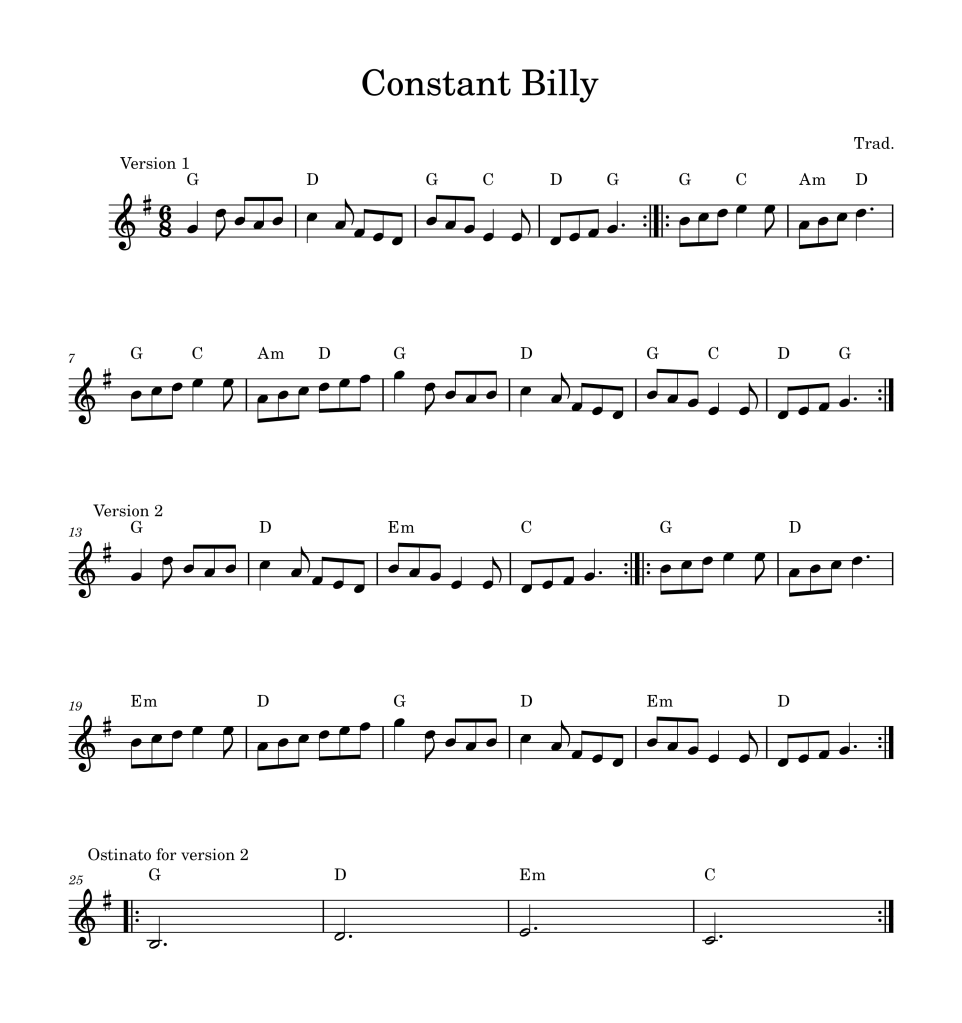

Tune with new chord sequence:

Extra task: try playing the tune in a different key, specifically A minor. Why?

1. Many tunes have more than one ‘standard’ key that they tend to be played in, and so being able to switch into a different key is a very useful skill to have in any setting. Examples of this are Cock of the North (G/A/D), Jump at the Sun (Gm/Em) and Mrs McCloud’s (G/A mixolydian).

2. Thinking in terms of intervals rather than in terms of fingerings/notes will make you more flexible as a musician. It’s good for your brain! I don’t expect many of you to be able to get it perfect first time, that’s not how learning music works, but practising this skill will also help to get the tune firmly into your memory banks.